A Minor a Novel of Love Music & Memory Kirkus Review

Symphony No. v in C minor, Op. 67 (1808)

The Basics

General Information

Composition dates: 1804-05, 1807-08; sketches 1805 (set aside for Sym. No. four).

Dedication: Prince Joseph Franz Maximilian Lobkowitz (also Wikipedia, and portrait) and Count Andrey Razumovsky (likewise Wikipedia, and portrait). Aforementioned dedicatees as Symphony No. 6.

Instrumentation (IV=added mvt. IV): Strings, MovieIv, 2 Fl, ii Ob, 2 Cl, 2 Bsn, CBsnIV, 2 Hn, 2 Tr, ATBTbnIv, Timp.

Starting time operation: 22 December 1808, Akademie at Theater-an-der-Wien. (Besides Sym. No. 6.)

Orchestra size for kickoff or early performance: 12-16.iii-iv.3-4.3-5/single winds.

Autograph Score: Staatsbibliothek, Berlin. Image available online.

First published parts: April 1809, Breitkopf und Härtel, Vienna. Image available at IMSLP and Beethoven-Haus.

First published score: May 1826, Breitkopf und Härtel, Vienna. Paradigm available at Beethoven-Haus. (Cohn)

Movements (Tempos. Keys. Forms.)

I. Allegro con brio (MM=108). C Minor. Sonata-Allegro.

2.Andante con moto (MM=92). A-flat major (Half dozen). Theme & Variation with a evolution.

III. Scherzo. Allegro (MM=96). C Minor/Major. Scherzo/Trio (ternary). Attacca to:

IV. Finale. Allegro (MM=84). C Major. Sonata-allegro.

Significance and Construction

In his epochal review of Beethoven's Symphony No. v in C minor, Op. 67, Eastward. T. A. Hoffman praised information technology as "ane of the virtually important works of the time." Its famous four-note opening gesture is not only credited as, "Fate knocks at the door" by Beethoven's factotum and biographer Anton Schindler, but also represents the "fate" that Beethoven wants to overcome during his lifetime, considering he was experiencing an increasing deafness, psychic hurting and depression. Beethoven wrote in a alphabetic character: "I will seize fate by the pharynx; it shall certainly not bend and crush me completely" (Lockwood, Beethoven Symphonies, 95). I of the aspects that makes the Fifth Symphony remarkable is that the "fate motif" is non treated as just a commencement theme. Instead, Beethoven put information technology throughout the entire piece—an obsessive repetition of the motif at dissimilar pitch levels, combined with interruptive stops that fight its restless momentum. (Lewanski, Beethoven and the Romantic Sublime.) Indeed, the "fate motif" is the about essential element of this symphony but it is not the merely thing that makes the Fifth Symphony great.

Beethoven started to sketch the Fifth Symphony in 1804, almost immediately following the completion of Symphony No. three, Eroica, only the composing progress was interrupted past several works such equally Fidelio, the 3 Razumovsky string quartets, and the Appassionata piano sonata. Beethoven finally completed the Fifth Symphony in 1808. It received its public premiere in Dec of that year, along with the 6th Symphony, Quaternary Pianoforte Concerto, Choral Fantasy, "Gloria" from the Mass in C, and a piano improvisation by Beethoven. During the long four-year period of composition Beethoven broke convention on several aspects. Well-nigh specially, it was the first symphony that Beethoven wrote in a minor key—C pocket-size. Minor-keyed symphonies were not unheard of, but were not the norm at the time. Mozart but composed two minor-manner symphonies, Nos. 25 and xl, both in K pocket-sized. The Eroica sketchbook shows a connection between the finale of No. 40 and the scherzo of the Fifth Symphony. (Lockwood, Beethoven's Symphonies, 97.) Merely ten of Haydn's over 100 symphonies were modest, most of them during his Sturm und Drang years 168-72. Of Haydn'south tardily symphonies, which would take been known to Beethoven, only one of the "Paris" (No. 83 in G minor) and 1 of the "London" symphonies, Symphony No. 95, is in minor. The latter may accept influenced Beethoven's choice of C minor, only this was a key of special importance to Beethoven. Charles Rosen was 1 of many commentators on Beethoven'southward "C-pocket-sized mood," stating,

Beethoven in C minor has come up to symbolize his artistic character. In every case, it reveals Beethoven equally Hero. C minor does not evidence Beethoven at his most subtle, merely information technology does give him to united states of america in his nearly extroverted form, where he seems to exist nigh impatient of any compromise. (Rosen, Beethoven's Piano Sonatas, 134.)

The similar "heroic grapheme" can be perceived in his other C pocket-sized multi-movement works, such equally the Pianoforte Sonata No. 8, "Pathetique", Cord Quartet, Op. xviii, no. 4, Pianoforte Concerto No. 3, Op. 37, and his last Piano Sonata, Op. 111.

Secondly, Beethoven experiments with different balances and goals of the symphonic cycle. For example, in the beginning movement, Beethoven gave essentially equal length to all four sections of the sonata form—exposition, development, recapitulation, coda—creating structural balance. Unlike codas in Classical symphonies, where the goal was to come to a quick conclusion, here the coda is lengthy and unstable, proceeding as a second development section. Furthermore, where the exposition presented an Eastward-flat major horn call followed by other major themes, suggesting the trouble will be solved in favor of C major in the recapitulation, the recapitulation weakens the solution by using the milder-toned bassoons for the horn call rather than asking the E-flat horns to change to C crooks, and, the C major closing theme is smashed by an insistent C-minor shift that remains for the entire, lengthy coda.

The enhancement of compositional weightiness of third and fourth movements emphasized Beethoven's emerging platonic of the movement bicycle conveying a teleological outlook related to the Bildungsroman , a Heroic or developmental novel that reemerged in the tardily eighteenth and early on nineteenth centuries. Beethoven's "fate motif" development and transformation from the first movement to the end of the third move and finally released in the finale certainly conveys the heroic ideal. Bringing it to a fulfilling decision, Beethoven connected the terminal two movements with an astonishing transition that generated enormous anticipation, with a gradual crescendo and additive instrumentation over insistent timpani finally bursting without intermission into the blazing, victorious finale. The attacca idea may have come from the fantasia genre—a freely adult sectional course equally understood in the late eighteenth century. The fantasia certainly influenced the episodic finale of the Eroica Symphony, every bit well as his Piano Fantasy, Op. 77 and Choral Fantasy, Op. 80, written at the same time. (Lockwood, Beethoven Symphonies, 113.)

Finally, the innovative application of instruments, particularly in the victorious finale, confirmed the status of the 5th Symphony. Trombones, contrabassoon and piccolo suddenly appeared at the last movement, enriching the sound and touch of the orchestra—it gets higher, lower, and louder. It was the first time that these instruments had been used together in a symphonic piece of work, and these instruments carried with them suggestion of military and sacred topoi. (This is discussed in detail in the essay "Beethoven'south Words" below. The ascending major triads played by the trombones at the finale'southward opening displayed a march-like phrase in C major, forth with the piccolo and contrabassoon, would be reminiscent of French overture/military music, and the alto, tenor, and bass trombone trio was connected to the sacred music tradition. All of this innovation stresses the sublime aesthetic, with a sense of triumph similar to that achieved in the "Hallelujah" of Beethoven'southward oratorio Christ on the Mount of Olives, Op. 85, composed at virtually the same time. (One can note the similarities of this and Beethoven'south Military Band in D, WoO 24, written in 1816.)

[We refer the reader to the following video performance for the ensuing discussion: Gardiner conducts Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique .]

The first movement begins with the characteristic "fate motive" (0:00-0:07). Instead of the usual more than melodic opening themes, the piece of work commences with a night and rhythmically varied theme; and dramatic the fermatas. Afterward the initial statement, the "drama-proper" begins with a series of urgent fate motives, played piano and imitated in the strings, earlier quickly reaching an outburst of tutti forte texture, where it finally develops beyond the initial motive, arriving at some other fermata. The rhythmic pulse of the fate motive pushes the story forward, creating a sense of urgency and inevitability. Well-nigh every measure of the symphony uses the fate motive in some form; it is short and tight in construction. 1 of the hallmarks of Romanticism was indeed the conflict between the private hero and larger forces, as the ubiquity of the fate motive surrounded by new materials suggests. A sense of rising in a higher place the struggle is given by an E-flat-major horn call (i:58-2:01) and dolce, hopeful, pastoral second theme in the strings (2:01-two:18), followed past a return to the original motive at present in E-flat major (2:26-2:35) to close the exposition.

In the development (2:36-3:50) a sense of teleology is achieved despite a relatively limited ready of keys and themes. Harmony is not the driving strength, but rather texture, orchestral color, and dynamics. For example, at the end of the development (3:xviii-three:50) the material is reduced from 4 voices to one vocalisation, and the main motive is reduced to just ii- and and then ane-annotation conversations between strings and winds. The recapitulation (iii:50-v:17) begins of a sudden, with the dormant feeling of the previous section bursting back into a thickened texture; the fate motive was waiting all forth to violently re-emerge! A brief respite from its violence is accomplished by a plaintive oboe solo (4:06-4:18), just this respite is only temporary. The promise of relief suggested by the C-major restatement of the E-flat themes from the exposition is thwarted past a sudden, sublime forcing of C pocket-size to begin a long, developmental coda (5:18-vi:40) which ends in the same manner the whole motion began. Heroic overcoming is saved for later. With all of the force, storminess, and twists contained in this movement, it is all the more astounding that Beethoven nigh perfectly balanced the four parts of the course—exposition development, recapitulation, coda—with each department being between 123 and 129 measures.

The 2nd movement (6:47-15:22) offers relief from the previous motion'southward incessant intensity and unfulfilled ending. Information technology begins piano with a noble, restrained theme in A-apartment in the lower strings (6:47-vii:40), before bursting into a cursory forte contrasting C-major militaristic theme, featuring trumpets and timpani (7:52-viii:14). The two main key centers of A-apartment and C mirror the get-go motility in which our hero was caught between ii exaggerated worlds—that of the C modest fate motive and the E-apartment major hopeful theme. The A-flat major section returns for a first variation, emphasizing the woodwind Harmoniemusik texture, before once more giving way to the C-major theme. After a brief A-flat minor passage (12:34-13:00),the first theme, once small and humble, returns purple and triumphant in a tutti, legato, and fortissimo texture (13:05-13:26); this is the first real moment in the symphony in which a sense of emotional reassurance has occurred. Furthermore, this and subsequent variations volition include only the A-apartment theme, non the militaristic C-major theme. As with the first movement, once again the victorious C major goal is promised, just unfulfilled. This move, like many second movements in pocket-sized-fundamental symphonies, gives a sense of respite and calm before the render of the storm.

The 3rd move (15:28-22:49)begins with mystery (xv:28-fifteen:48) in the low strings (as the second motility had begun), followed past the movement'southward chief thought: the horns boom a telephone call to activity (15:48-xv:54) consisting of the original short-short-short-long rhythmic motive, clearly related to the fate motive of the first movement. Beethoven'southward sketches evidence that the first and tertiary movements were the ii first conceived. (Lockwood, Beethoven's Symphonies, 100.) Although the movement does not acquit the title "scherzo" (only the tempo marking "allegro" is given in the score), all of the elements of a Beethoven scherzo are present: the tempo is quick, misplaced accents, and changing, unbalanced phrase lengths throughout. From a formal standpoint, this motility follows the structural models of the dance movements of the past, just the earliest manuscripts prove that Beethoven originally intended for it to be in five parts, every bit he did in the scherzo movement in the Fourth Symphony. Past the first publication of the parts in 1809, still, Beethoven shortened the scherzo into three parts, without full repeats of the scherzo-trio before the final re-written scherzo bridge to the finale. (Note: the total five-part form of the earliest performances is followed in the video performance referred to in this discussion.) The most notable aspect of the scherzo comes in the trio (17:05-18:twenty), where instead of the usual pastoral character with accent on the winds, Beethoven provided a brilliant and energetic fugue in C major, continuing the narrative between C modest and C major that has been present throughout the symphony. The apply of a fugue not only pushes forwards the excitement and tension, it also suggests a sacred topic in a musical section that is traditionally very secular, even rustic, giving the tertiary movement a surprising seriousness that, in turn adds weight and importance. This teleological approach is only intensified past the render of a hushed, anticipatory re-writing of the scherzo, as the short-brusque-curt-long fanfare theme is played past solo woodwinds andpizzicato strings(21:32-22:02) and the motive continues subtly in timpani (22:17-22:xx), as if to remind us that the battle is non over, and something is nevertheless to come. This serves every bit a bridge to the finale.

George Grove characterizes the tension building bridge passage of the scherzo (22:27-22:49) leading to the victorious (finally!) C-major finale movement (22:49-end) this style: "To hear it is like being present at the work of Creation." (Grove, Beethoven and His Ix Symphonies, 172.) During the bridge, the violins climb slowly out of C minor past an virtually imperceptive E-natural of C major, leading to a crescendo and gradual addition of all of the instruments, finally launching into the fourth motility without a pause. The element of victory that is so frequently tied to the Fifth Symphony must surely come from this moment: the triumphant march presented by the full orchestra, now complete with piccolo, contrabassoon, and three trombones, seems to declare, if non outright celebrates the assertion of C major over C minor. At that place are iv new themes presented in the exposition of the quaternary motion, all of which are presented in a major central and have connections to material presented throughout the previous 3 movements. The third (23:47-24:13) and 4th (24:13-24:35) themes both characteristic the short-short-short-long motive. Yet, a literal remember of substantial thematic material, rather than just the pervasive motive, comes in the development (26:33-28:45), when Beethoven returns to the material of the scherzo and span and with it the key of C small-scale (28:15-28:45). This recall has become "one of the most famous moments in symphonic literature", and even critics of the Fifth Symphony conceded that information technology was an act of genius. (Lockwood, Beethoven'southward Symphonies, 113.) Non simply does information technology further serve Beethoven'due south cyclical integration of all four movements, just it also extends the hero's narrative; past bringing back the primal of C minor and reminding u.s. of the struggles previously heard, Beethoven allows for an even greater sense of victory and overcoming in the recapitulation (28:45-31:07), in which all four themes come up dorsum relentlessly in the key of C major. The coda (31:07-end) that follows is one of the longest Beethoven ever wrote and remains in the key of C major the unabridged fourth dimension; in fact, subsequently the brief render of the scherzo, the slice remains in C major until the finish. The 2d function of the coda (32:06-terminate) is marked by an increase in tempo: nosotros hear the fourth theme, but subconscious within the repetitions of this motive is also the rising triadic showtime theme! The tempo increases, and Beethoven is seemingly pushing us to the end, hammering the tonic C-major chord over and over once more at the end until the unabridged orchestra finally plays a unison C in the final bar. Per ardua advertizement astra, through struggle to the stars, our hero'south journey ends in victory.

—Contributors: EH, SH, ST, SY, MER

Beethoven'south Words

"The concluding movement in the symphony is with iii trombones and flautini [piccolos]—though not with 3 kettledrums, but will brand more noise than half-dozen kettledrums and ameliorate noise at that-." Letter written to Count Franz von Oppersdorff, March, 1808. (Thayer,Thayer's Life of Beethoven, Vol. 1., 433.)

Beethoven'southward quote suggests that he and Count Oppersdorff had previous correspondence on the instrumentation necessary to "make more noise" in the finale of the Fifth Symphony. The determination to delay the entrance of piccolo, contrabassoon and trombones until the final move allows the finale to burst forth in an overwhelming assertion of joy, sweeping away the ominous presence of the previous 3 movements. These particular instruments besides change the entire soundscape of the orchestra by opening upwardly its range, both an entire octave higher (piccolo) and lower (contrabassoon) in the woodwinds, increasing the book dramatically with three trombones, and giving it a military band grapheme. Their inclusion changes the foreboding march of "Fate" into a triumphal and enthusiastic anthem of victory for the finale.

Beethoven's desire to arrive at the war machine sound of a march in the finale of his Fifth Symphony could partly be due to a ascent of local patriotism from Federal republic of germany and Austria's repeated losses to France. In 1807, a large office of Deutschland was lost to the French with the Treaty of Tilsit and Beethoven's own anti-French sentiments were at an all-fourth dimension high. He remarked to a friend at this time, "I too would like to . . . bulldoze them away from where they have no right to be." (Solomon, Beethoven, 264.) He also exclaimed to the violinist Krumpholz, "Pity that I do not understand the art of war as well as I practice the art of music; I should yet conquer Napoleon!", afterward learning of Napoleon'due south victory at Jena (Kerst & Krehbiel, "Beethoven: The Human and the Artist, As Revealed in his own Words," north. 161).

To Beethoven and his audience in 1808, the piccolo was a standard instrument for a marching ring, but virtually unknown in symphonic compositions. Run across the prototype above depicting a French war machine band ca. 1806. Beethoven was the first composer to include the piccolo in symphonic works. (Teng, Kuo-Jen."The Function of the Piccolo in Beethoven's Orchestration," three.) When he did utilize it, it was sparingly and e'er associated with military/soldierly topics, such as the triumphal finale of the Fifth Symphony, the Turkish March in the finale of the Ninth Symphony, and the coda of the Overture to Egmont, Op. 84. At ane other time, in the thunderstorm of the Sixth Symphony, the piccolo imitates the whistling of the wind. The contrabassoon was probably a familiar audio in symphonic compositions, as evidence suggests information technology was likely used at times, in large orchestras, to double the audio of the violones/double basses. Only its distinctive deep and reedy audio could also be heard in military bands. Beethoven used piccolo and contrabassoon for his ain marches for war machine band marches, such equally his "Für die Böhmische Landwehr" ("For the Bohemian Ward"), WoO 18 (1809) which is scored for piccolo, contrabassoon, 2 flutes, 3 clarinets (C & F), two trumpets, 2 french horns, 2 bassoons and percussion, and "Pferde Musik" ("Equus caballus-music"), WoO nineteen (1810) scored for piccolo, contrabassoon, 2 flutes, 3 clarinets (C & F), 2 trumpets, ii french horns, 2 bassoons and percussion. The march-similar rhythms and the use of characteristic marching ring instruments in the finale helps to emphasize the sense of a triumphal victory after a peachy struggle.

The iii-trombone choir—alto, tenor and bass—similarly carried specific topical connotations based on their historical use as doubling choral parts in sacred vocal music. For centuries this type of trombone choir was virtually synonymous with sacred music, particularly in the German language-speaking globe. Some of Beethoven's contemporaries in Vienna who had recently written religious works using that same trombone choir to double the chorus, including Antonin Reicha'due south (teacher of Liszt, Berlioz, and Franck) Missa pro defunctis (1803-09), and Antonio Salieri's (teacher of Beethoven, Schubert and Liszt) Requiem in C small (1804). (See Trombone History: 19th Century.)

By understanding the song-similar history of the trombone choir, it becomes particularly interesting to note how Beethoven used the trombones in the 5th Symphony. After the march-like opening theme, instead of matching the marching rhythms played by the rest of the orchestra, the trombones sing forth their parts in a choir-like manner through the emphasis of long powerful chords and dramatic entrances. This unique vocal choir apply of the trombones could possibly exist the germination of Beethoven'southward revolutionary thought to utilize a vocal choir in his 9th Symphony.

Besides the abundance of march music and Beethoven's own utilize of piccolo and contrabassoon in his works for military band, and the plethora of sacred music using the iii-trombone choir, many operas of the late eighteenth century besides used these instruments for topical scenic enhancement. Notably, Mozart's Idomeneo, Don Giovanni, and Die Zauberflöte all include the alto-tenor-bass trombone trio in scenes depicting supernatural elements. The Fifth Symphony'southward unprecedented instrumentation in the final move finer changes the bright and boisterous march into a militaristic anthem of victory, simply, as in the bang-up heroic stories of the middle ages, there is a religious side to these stories as well, with the conservancy of the hero being office of his journeying. So Beethoven, every bit was his genius, uses instrumentation as one of the tools that brings the symphonic genre ever closer to bona fide dramatic works, and though the Fifth Symphony does not celebrate whatsoever particular country or private, it celebrates the power of overcoming and the victory of the cocky, and the soul.

—Contributors: FJ, JM, MER

Others' Words

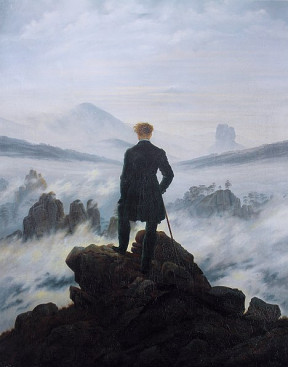

E. T. A. Hoffmann was one of the most influential and creative writers of the early nineteenth century whose literature oft emphasized and critiqued romantic aesthetic values. A versatile artist, he was also a music critic, lawyer, composer, usher, musician, and painter. Among his many submissions to the Allgemeine musikalisches Zeitung include "Beethoven'south Instrumental Music" of 1810, revised in 1813 every bit part of the collection Kreisleriana . (Here is an article about information technology by Arthur Ware Locke from Musical Quarterly in 1917, with a translation of the text.) In this widely quoted critical essay, Hoffmann commends Beethoven's Symphony No. 5 and instrumental music more generally as model vehicles for deep and powerful emotional expressivity, and therefore the summit of Romantic arts. The following translated excerpts compare Beethoven's music to Haydn'southward and Mozart's, and requite a colorful description of Beethoven'south Fifth Symphony. In the spirit of the multi-sensory nature of Hoffmann'south works, nosotros have provided paintings (which are linked to data) and links to musical examples that illustrate Hoffmann'south points, details, and description.

On Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven:

"Mozart and Haydn, the creators of the instrumental music of today, prove us the art for the start time in its full glory; the 1 who has looked on it with an all-embracing love and penetrated its inmost existence is—Beethoven! The instrumental compositions of all 3  masters breathe the same romantic spirit, which lies in a similar deep understanding of the essential property of the art; there is nevertheless a decided difference in the character of their compositions. The expression of a child-like joyous spirit predominates in those of Haydn. His symphonies lead united states of america through dizzying green woods, among a merry, gay oversupply of happy people. Immature men and maidens pass past dancing; laughing children peeping from behind trees and rose-bushes playfully throw flowers at one some other.

masters breathe the same romantic spirit, which lies in a similar deep understanding of the essential property of the art; there is nevertheless a decided difference in the character of their compositions. The expression of a child-like joyous spirit predominates in those of Haydn. His symphonies lead united states of america through dizzying green woods, among a merry, gay oversupply of happy people. Immature men and maidens pass past dancing; laughing children peeping from behind trees and rose-bushes playfully throw flowers at one some other.

"A life full of love, of felicity, eternally young, every bit before the fall; no suffering, no sorrow, just a sweet melancholy longing for the beloved course that floats in the distance in the glow of the sunset, neither budgeted nor vanishing, and equally long as it is there night will not come for it is itself the evening glow which shines over mountain and wood .

"A life full of love, of felicity, eternally young, every bit before the fall; no suffering, no sorrow, just a sweet melancholy longing for the beloved course that floats in the distance in the glow of the sunset, neither budgeted nor vanishing, and equally long as it is there night will not come for it is itself the evening glow which shines over mountain and wood .

"Mozart leads us into the depths of the spirit world. We are seized by a sort of gentle fear which is really only the presentiment of the infinite. Dearest and melancholy audio in the pure spirit voices; night vanishes in a brilliant regal glow and with inexpressible longing we follow the forms which, with friendly gestures, invite u.s.a. into their ranks as they fly through the clouds in the never-ending dance of the spheres.

"Mozart leads us into the depths of the spirit world. We are seized by a sort of gentle fear which is really only the presentiment of the infinite. Dearest and melancholy audio in the pure spirit voices; night vanishes in a brilliant regal glow and with inexpressible longing we follow the forms which, with friendly gestures, invite u.s.a. into their ranks as they fly through the clouds in the never-ending dance of the spheres.

"In the same way Beethoven'south instrumental music discloses to us the realm of the tragic and the illimitable. Glowing beams pierce the deep night of this realm and we are conscious of gigantic shadows which, alternately increasing and decreasing, close in on us nearer and nearer, destroying us simply not destroying the pain of endless longing in which is engulfed and lost every passion aroused by the exulting sounds. And just through this very hurting in which love, hope, and joy, consumed but not destroyed,

Glowing beams pierce the deep night of this realm and we are conscious of gigantic shadows which, alternately increasing and decreasing, close in on us nearer and nearer, destroying us simply not destroying the pain of endless longing in which is engulfed and lost every passion aroused by the exulting sounds. And just through this very hurting in which love, hope, and joy, consumed but not destroyed, ![]() burst along from our hearts in the deep-voiced harmony of all the passions, practice nosotros continue living and become hypnotized seers of visions!

burst along from our hearts in the deep-voiced harmony of all the passions, practice nosotros continue living and become hypnotized seers of visions!

An appreciation of romantic qualities in fine art is uncommon; romantic talent is still rarer. Consequently there are few indeed who are able to play on that lyre the tones of which unfold the wonderful region of romanticism.

"Haydn conceives romantically that which is distinctly human being in the life of homo; he is, in and then far, more comprehensible to the majority.

"Haydn conceives romantically that which is distinctly human being in the life of homo; he is, in and then far, more comprehensible to the majority.

Mozart grasps more than the superhuman, the miraculous, which dwells in the imagination.

Beethoven's music stirs the mists of fear, of horror, of terror, of grief, and awakens that  endless longing which is the very essence of romanticism. He is consequently a purely romantic composer, and is it non possible that for this very reason he is less successful in vocal music which does not surrender itself to the characterization of indefinite emotions merely portrays effects specified by the words rather than those indefinite emotions experienced in the realm of the infinite?"

endless longing which is the very essence of romanticism. He is consequently a purely romantic composer, and is it non possible that for this very reason he is less successful in vocal music which does not surrender itself to the characterization of indefinite emotions merely portrays effects specified by the words rather than those indefinite emotions experienced in the realm of the infinite?"

On Symphony No. 5:

"What instrumental piece of work of Beethoven testifies to this to a college degree than the immeasurably noble and profound Symphony in C pocket-sized? How this marvelous composition carries the hearer irresistibly with it in its ever-mounting climax into the spirit kingdom of the space! What could exist simpler than the main motive of the first allegro equanimous of a mere rhythmic effigy which, kickoff in unison, does not even betoken the central to the listener. The character of anxious, restless longing which this portion carries with it just brings out more clearly the melodiousness of the second theme!—It appears as if the breast, burdened and oppressed past the premonition of tragedy, of threatening annihilation, in gasping tones was struggling with all its forcefulness for air; but before long a friendly form draws near and lightens the gruesome night. . . . How simple—let us repeat once again—is the theme which the master has made the footing of the whole piece of work, but how marvelously all the subordinate themes and bridge passages relate themselves rhythmically to it, so that they continually serve to disclose more and more than the grapheme of the allegro indicated by the leading motive. All the themes are brusk, well-nigh all consisting of but two or 3 measures, and as well that they are allotted with increasing diverseness first to the wind then to the stringed instruments. One would call back that something disjointed and confused would result from such elements; merely, on the contrary, this very organization of the whole work as well every bit the constant reappearances of the motives and harmonic effects, following closely on one another, intensify to the highest caste that feeling of inexpressible longing. Aside from the fact that the contrapuntal treatment testifies to a thorough study of the art, the connecting links, the constant allusions to the primary theme, demonstrate how the keen Master had conceived the whole and planned information technology with all its emotional forces in mind.

"Does not the lovely theme of the Andante con moto in A-flat audio like a pure spirit voice which fills our souls with hope and comfort?—But here also that terrible phantom which alarmed and possessed our souls in the Allegro instantly steps along to threaten united states from the thunderclouds into which it had disappeared, and the friendly forms which surrounded us flee quickly before the lightning.

"What shall I say of the Minuet? Notice the originality of the modulations, the cadences on the dominant major chord which the bass takes up as the tonic of the continuing theme in pocket-sized—and the extension of the theme itself with the looping on of extra measures. Exercise you non experience again that restless, nameless longing, that premonition of the wonderful spirit-world in which the Master holds sway? But like dazzling sunlight the splendid theme of the last motion bursts forth in the exulting chorus of the full orchestra. What wonderful contrapuntal inter-weavings bind the whole together. It is possible that it may all sound simply similar an inspired rhapsody to many, but surely the heart of every sensitive listener volition be moved deeply and spiritually past a feeling which is none other than that nameless premonitory longing; and up to the last chord, yeah, even in the moment after it is finished, he will not exist able to detach himself from that wonderful imaginary globe where he has been held captive by this tonal expression of sorrow and joy. In regard to the structure of the themes, their evolution and instrumentation, and the way they are related to one another, everything is worked out from a central point-of-view; just information technology is specially the inner human relationship of the themes with one another which produces that unity which alone is able to concord the listener in one mood. This relationship is often quite obvious to the listener when he hears information technology in the combination of two themes or discovers in dissimilar themes a common bass, but a more than subtle relationship, not demonstrated in this way, shows itself merely in the spiritual connection of ane theme with another, and it is exactly this subtle relationship of the themes which dominates both allegros and the Minuet—and proclaims the self-conscious genius of the Master."

—Contributors: AL, LB, YLi, MER

Topics and readings for further inquiry

Regional History (1806)

Full general Research Division, The New York Public Library. "France, 1806" New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed July 20, 2020.

Hicks, Peter, "Why did the battle of Jena take place?" Napoleon.org.

A great overview of the political and militaries problems leading upwardly to the boxing of Jena.

Beethoven in his ain words

Kerst, Friedrich and Krehbiel, Henry Edward, "Beethoven: The Man and the Artist, As Revealed in his own Words."

A collection of various quotes and writings by Beethoven, organized into diverse topics regarding his views: on composing, on performing music, on his own works, etc.

Beethoven and Schindler

Albrecht, Theodore.".Anton Schindler as destroyer and forger of Beethoven's chat books: A instance for decriminalization."Music'due south intellectual history (2009): 169-82. Available online at rilm.org.

Roles of Piccolo and Trombone in symphonic music

Kimball, Will. "Trombone History: 19th Century (1801-1825)." kimballtrombone.com.

A very extensive and well researched website on the history and usage of the trombone. Page hosted past trombonist Will Kimball.

Teng, Kuo-Jen. "The Role of the Piccolo in Beethoven's Orchestration." DMA dissertation. Digital Library UNT.

A doctoral dissertation on the function of the piccolo in Beethoven'southward symphonic works.

On Fate and musical meaning

Guerrieri, Matthew. The First Four Notes: Beethoven's Fifth and the Human Imagination . New York: Vintage Books, 2014.

Guerrieri goes through the many musical and extra-musical associations of Beethoven's opening motive, bringing in history, philosophy, art, and social theory into a multi-dimensional exploration of this famous musical moment.

"Beethoven's Fifth Symphony: the Truth Near the 'Symphony of Fate'". Deustch Welle. Accessed 07/20/2020.

Beethoven, Romanticism, the Sublime, E.T.A. Hoffmann

Lewanski, Michael. "Beethoven and the Romantic Sublime: The Fifth Symphony." www.michaellewanski.com. Accessed 07/24/2020.

Beethoven and the "C-minor Mood"

"Beethoven and C minor." Wikiwand. Accessed 07/25/2020

Rosen, Charles. Beethoven's Piano Sonatas: A Curt Companion. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002.

Online Resources

Early Editions of Score and Parts

Shorthand score

Outset Consummate Scholar Edition. Ludwig van Beethovens Werke, Serie i: Symphonien, Nr.v.Leipzig: Breitkopf und Härtel, n.d.[1862]. Plate B.v.

Parts: First Edition. Leipzig: Breitkopf und Härtel, north.d.[1809]. Plate 1329.

Modernistic Edition of the Score

1989 Dover Edition. Reprint of the Braunschweig: Henry Litolff's Verlag, No. 2769, n.d. (ca.1880)

1976 Dover Edition (Reprint of the edition by Leipzig: Ernst Eulenburg, n.d. [1938])

New York Philharmonic score with annotations by Leonard Bernstein.

New York Philharmonic score with annotations by Artur Rodzinski.

New York Philharmonic score with annotations by Erich Leinsdorf.

Recordings available online

Period/HIP Performances—

Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique, Gardiner

1st movement, second motion, tertiary motion, 4th movement

Video: Gardiner conducts Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique .

Hanover Ring, Goodman and Huggett

1st movement, second movement, tertiary movement, 4th movement

The outset consummate prepare of the Nine Symphonies to be issued on original instruments.

The London Classical Players, Norrington

1st movement, 2nd motion, 3rd movement, 4th movement

Amongst the primeval complete set of the Nine Symphonies issued on original instruments, recorded in the late-1980s, several years later on Hanover Ring'south recording.

MusicAeterna, Currentzis

1st move, second motility, tertiary movement, quaternary movement

Every musical gesture is exaggeratedly interpreted, total of Currentzis's personality, a transcendent recording.

Concentus Musicus Wien, Harnoncourt

1st movement, 2nd motion, tertiary movement, fourth motility

One of the last recordings of the maestro. Different than the complete symphony set with Europe Chamber Orchestra.

Orchestra of the 18th Century, Brüggen

1st motility, 2nd motion, third move, 4th movement

Complete Set of Beethoven Symphonies by Orchestra of the 18th Century and Brüggen

Important Recordings by Modern Orchestras—

London Philharmonic Orchestra, Weingartner

1st movement, 2nd move, third and 4th movements

1 of the primeval commercial recordings in history of Beethoven Fifth Symphony.

Philharmonic Orchestra, Klemperer

1st movement, second movement, tertiary movement, fourth movement

Typical mid 20th-century interpretation with heavy audio and slow tempo.

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, Rattle

1st motility, 2d motion, 3rd movement, 4th move

VPO's not-so-common historically informed interpretation, with Simon Rattle talking about this symphony at the beginning of the video.

Vienna Combo Orchestra, Thielemann

1st movement, 2d motility, third movement, 4th movement

Probably VPO's most important Beethoven symphonies cycle during the starting time 20 years of the new century. Representative interpretation of the then-called German language-Austrian tradition.

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, Kleiber

1st movement, 2nd motility, third movement, 4th motility

One of the about famous Beethoven Fifth Symphony recordings that Deutsche Grammophon has ever issued and one of the very few commercial recordings by Carlos Kleiber the legend.

Tonhalle-Orchester Zürich, Zinman

1st movement, 2nd movement, 3rd movement, 4th movement

Tonhalle-Orchester Zuürich is a modern orchestra, simply Zinman persuades them to make a transparent audio which sounds similar a catamenia instrument ensemble.

Royal Flemish Philharmonic Orchestra, Herreweghe

1st motion, 2nd movement, third motion, 4th motility

Complete Set of Beethoven Symphonies by RFRO and Herreweghe

Mod orchestra led by one of the almost important early music experts of our time.

Descriptions available online (videos, programme notes, etc.,)

Roger Norrington talks about Beethoven 5th Symphony

In German.

Beethoven Fifth Symphony: Assay by Gerard Schwarz

Symphony No. v: Subversive subtexts | Gardiner and the ORR on Beethoven'southward Symphonies

Graphic score, for site visitors who practise not read music.

1st movement, 2nd movement, 3rd movement, 4th motion

How a Bully Symphony was Written

Leonard Bernstein'due south famous word of Beethoven'southward Fifth Symphony, starting time move compositional process, available on youtube.

Rehearsal, Sleeping room Orchestra of Europe with N. Harnoncourt.

Includes discussion of sources, functioning considerations.

Marianne Williams Tobias, Plan notes, Indianapolis Symphony.

P.D.Q. Bach (Peter Schickele) – "New horizons in music appreciation" (Beethoven)

A comical assay of the offset movement of the Fifth Symphony by Peter Schickele.

salernocamprow1974.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.esm.rochester.edu/beethoven/symphony-no-5/

0 Response to "A Minor a Novel of Love Music & Memory Kirkus Review"

Post a Comment